The Determination of the Likelihood of Confusion between Weak Trademarks-Based on the OATLY Case in the UK and the Chinese Characters (味全總舖師) Case in Taiwan

[ NEWSLETTER September 2022 ] >Back| Trademark | |||||

| I.The Determination of the Likelihood of Confusion between Weak Trademarks-Based on the OATLY Case in the UK and the Chinese Characters (味全總舖師) Case in Taiwan | |||||

|

Generally, the likelihood of confusion relates to the distinctiveness of the marks at issue. The lower the distinctiveness of the marks is, the harder the likelihood of confusion will be. A mark with a fanciful or coined term is per se distinctive. On the other hand, a mark with only descriptive, generic, or highly suggestive terms is less distinctive, i.e., a weak mark. However, an originally weak mark may become distinctive through use in the market. The question is: will the determination of the likelihood of confusion be affected by how the mark becomes distinctive? We discuss by the following two cases.

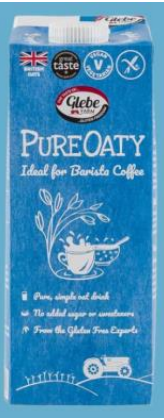

OATLY case, namely OATLY AB v Glebe Farm Foods Limited [2021] EWHC 2189 (IPEC), provides a detailed process for determining whether the likelihood of confusion exists between weak marks. The Chinese Characters (味全總舖師) case in Taiwan shares similar facts with the OATLY case, but the verdict is completely reversed. OATLY is a trademark owned by OATLY AB registered for dairy substitutes and oat-based drinks. OATLY products have a high market share in the UK, which have established a highly distinctive character and reputation for the “OATLY” brand. OATLY AB took Glebe Farm Foods to the court, alleging that Glebe had infringed the “OATLY” trademark by selling oat milk called "PUREOATY". The marks used by both parties are shown below. |

|||||

|

|||||

| The Intellectual Property Enterprise Court (the UK court), which is a specialist court part of the Business and Property Courts of the High Court of Justice, listed guidance with regard to the approach to assessing a likelihood of confusion as follows: | |||||

| a. | The likelihood of confusion must be appreciated globally, taking account of all relevant factors. | ||||

| b. |

The likelihood of confusion is assessed by the average consumer of the named goods who, although being reasonable and prudent, does not compare trademarks side by side and often rely upon one’s imperfect recollection to purchase. In other words, the consumer perceives a trademark as a whole, getting an overall impression, and does not analyze its various details.

|

||||

| c. | In a general matter, the visual, aural and conceptual similarities of the marks must be compared by their overall impressions. However, if all other components of a complex trademark are negligible, we may make the comparison solely by the dominant elements. Moreover, if an element corresponds to a registered trademark, it may retain an independent distinctive role in a composite mark even though it does not constitute a dominant element of the mark. | ||||

| d. | A lesser degree of similarity between the goods may be offset by a greater degree of similarity between the marks, and vice versa. | ||||

| e. | The lower the distinctiveness is, the harder it is to establish similarity and vice versa. There is a greater likelihood of confusion if the registered trademark has a highly distinctive character, either per se or by the use of it. If the similarity between the respective trademarks is a generic element in relation to the goods for which they are registered, that points against there being a likelihood of confusion. | ||||

| f. | If the association between the marks causes the public to wrongly believe that the respective goods come from the same or economically-linked undertakings, there is a likelihood of confusion. | ||||

| Based on the guidance listed before, the UK court compared “OATLY” with “PUREOATY” and found that there is no visual similarity. Indeed they share the same word “oat”. However, the marks have different lengths in letters, and also the additional word “PURE” at the start of the mark detracts the average consumer significantly from the visual similarity. There is no aural similarity for the same reason. As to the conceptual similarity, OATLY AB argued that “PURE” is merely a descriptive word and thus the consumer will only focus on “OATY”, which is highly similar to the plaintiff’s “OATLY” trademark. The UK court disagreed, stating that “OATLY” is also descriptive in relation to a generic word “oat”, and the suffix “ly” does not change the literal meaning of the word. On this basis, any conceptual similarity between the marks is based on their common reference to “oat”, not to “OATLY”. Namely, the conceptual similarity of “OATLY” and “PUREOATY” is attributable to their descriptiveness. The UK court cited several precedent cases which emphasized the difficulty in establishing any likelihood of confusion if the similarity lies in a commonality of descriptive elements. In Reed Executive Plc v Reed Business Information Ltd [2004] EWCA Civ 159 at [83]–[84] the Court of Appeal said:“...where you have something largely descriptive the average consumer will recognize that to be so, expect others to use similar descriptive marks and thus be alert to details which would differentiate one provider from another.” Generally, the overall impression of a mark is mainly created by its dominant elements, except the dominant elements are descriptive. Under this circumstance, the consumers will pay more attention to any details which may help them to distinguish between brands. In such cases, subordinate elements of a mark will have more weight than they would have been in general cases with regard to the determination of the likelihood of confusion. For these reasons, the UK court gave more weight to the word “PURE” and found that there is no likelihood of confusion between the “PUREOATY” and “OATLY”, accordingly rejecting OATLY AB’s claim. There is a very similar case named Case No. 70 determined by the Intellectual Property and Commercial Court in Taiwan (the Taiwan court) in 2019. We introduce the case as follows. The plaintiff owns a “總舖師 (means “executive chief” in Taiwanese)” trademark registered in the goods “dumplings”. The intervener filed an application for a mark “味全總舖師 (“味全(Wei Chuan)” conveys no specific meaning and “總舖師” means “executive chief” in Taiwanese)” sought to be registered in the same goods “dumplings”. The plaintiff filed an opposition to the registration for similarity, and the Taiwan Intellectual Property Office (TIPO) ruled against the opposition. The case went to the Taiwan court. |

|||||

| The non-dispute facts go as follows. | |||||

| a. | 總舖師” is a common honorific for executive chef and thus a descriptive term in food-related goods. On the application, the plaintiff disclaimed the entire term “總舖師(executive chief)” in order to be registered. | ||||

| b. | The marks share the same dominant element “總舖師(executive chief)” and the same category of goods. | ||||

| c. | In Taiwan, “味全(Wei Chuan)” is a famous company name and also a well-known trademark which has a long and profound history in the field of food and drink in Taiwan. | ||||

| The issue here is how much weight the court should give to the word “味全(Wei Chuan)” in the determination of the likelihood of confusion. | |||||

|

|

|||||

| TIPO argued that there is no likelihood of confusion because “味全(Wei Chuan)” mark has a distinctive character and national-wide reputation. However, the Taiwan court ruled in an opposite way. “總舖師(executive chief)” establishes its highly distinctive character by the use for decades. Both parties’ marks contain the same dominant element“總舖師(executive chief)”. Although the alleged infringing mark “味全總舖師(Wei Chuan executive chief)” consists of five Chinese characters while the alleged infringed trademark“總舖師(executive chief)”consists of three, “味全(Wei Chuan)” is the name of a company and has no semantic meaning with “總舖師(executive chief)”. Consumers may divide the alleged infringing mark into two parts: “味全(Wei Chuan)” and “總舖師(executive chief)”. Thus, high similarity exists. Accordingly, the Taiwan court ruled to revoke the registration of “味全總舖師(Wei Chuan executive chief)”. In the “OATLY” case and the “總舖師(executive chief)” case, the alleged infringed trademarks were both descriptive words and were weak distinctive at the beginning, but they became distinctive through long-term and wide use for decades. The alleged infringing marks are both composite mark sharing the same dominant element of the alleged infringed trademarks. Compared with “PUREOATY”, “味全總舖師(Wei Chuan executive chief)” has two advantages in the judgment of the likelihood of confusion. First, the word “總舖師(executive chief)” had been disclaimed, while “OATLY” had not. Second, “味全” is a fanciful term and a well-known trademark, while “PURE” is merely a descriptive word. However, the verdicts go the opposite way. The main difference is that the UK court gave less weight to the dominant element “OATLY” in view of its descriptive nature, while the Taiwan court gave more weigh to “總舖師(executive chief)” in view of its high distinctiveness obtained by long-term use in Taiwan. The determination of the existence of a likelihood of confusion is never an easy job because “likelihood”, “similarity” and “confusion” are legal concepts as uncertain as “reasonable”. Without a clear standard established by consistent judgments, it’s hard for practitioners to accurately predict the outcome, not to mention lay persons. The standard need to be established by the court through a detailed, deliberate process of reasoning, thereby reducing disputes and safeguarding the rights and interests of the trademark owners. Therefore, the cases introduced above are worth taking as reference for practitioners and the Intellectual Property and Commercial Court in Taiwan. |

|||||

|

||